Architecture

Malmö Konsthall is one of Europe’s largest exhibition spaces for contemporary art and an internationally renowned example of Nordic modernism. It is a place where light, space, and art meet. The building opened on March 22, 1975, after a long process in which the dream of an art hall in Malmö finally became a reality.

An idea that took decades to realize

As early as 1931, several members of the Skåne Art Association took the initiative to establish an art hall in the city. They formed a foundation and organized a large goods lottery to finance the project, but the plans were never realized. During the 1960s and early 1970s, the discussions gained new momentum. The social climate, along with the recurring cultural-debate slogan “Art to the people,” once again highlighted the need for an open exhibition space for contemporary art – a place where the people of Malmö could encounter art without barriers. In 1971, the City of Malmö decided to establish a municipal art hall and announced an architectural competition.

Klas Anshelm and the Vision of Light, Simplicity, and Flexibility

The competition was won by architect Klas Anshelm, who had previously gained recognition for Lunds Konsthall and his buildings for Lund University. Inspired by the activity centers that had emerged in his hometown of Lund during the 1960s, he envisioned a building that was robust, flexible, and generous in its architecture. For Malmö Konsthall, he articulated a clear idea of directness and openness:

“I think it is important that you enter an art hall directly. As soon as you step through the front doors, you should be surrounded by the art. I want people to be able to nail into the floors and walls without anything being damaged.”

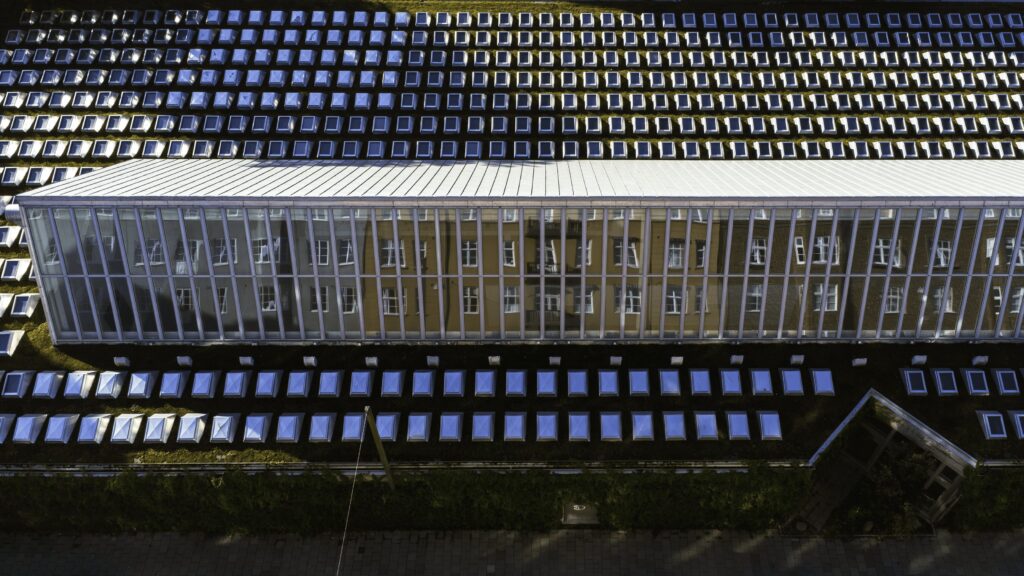

The result was a large, bright, and flexible exhibition space – essentially a simple, white “box” that gives artists great freedom. Almost any spatial idea can be realized within the room, which has made the building particularly appreciated by exhibiting artists. One of the hall’s most distinctive features is its 550 skylights, a solution Anshelm developed while working on ideas for the Nordic Pavilion at the 1961 Venice Biennale. Although he did not receive the commission for Venice, he realized the concept at Malmö Konsthall instead. The skylights create a soft, even daylight that continues to attract interest from architecture enthusiasts around the world.

Change and Renewal

In 1994, the art hall underwent an extensive renovation and expansion designed by architect Jan Holmgren of White Arkitekter. The new section, called “Mellanrummet” (The In-Between Space), connects the exhibition hall with the former Hantverkshuset from 1915. Here, the reception, café, and auditorium – and today also Malmö Konsthall’s bookshop – were placed, freeing up more space for art and giving the building a clearer structure and improved flow.

Klas Anshelm (born 1914) became one of Sweden’s leading architects during the post-war period and left a significant mark on Swedish and Scanian architectural history. With his unique style and ability to combine tradition and modernism, he created a number of iconic buildings, particularly in southern Sweden.

Anshelm was born in Gothenburg and trained as an architect at Chalmers University of Technology, graduating in 1940. He began his career working for the renowned architect Hans Westman in Lund, a period that greatly influenced his early work. After a few years in Stockholm, Klas Anshelm returned to Lund in 1947 to establish his own office. The move was made on the recommendation of Gunnar Wejke, then head of the Building Board’s Planning Department, as Lund University was facing an expansion and there was a great need for new buildings.

During the 1950s and 1960s, in addition to projects related to Lund University, Anshelm was involved in several major undertakings, including the City Hall in Lund and the design of Lunds Konsthall. These projects established his reputation as a skilled, confident, and innovative architect, while also demonstrating his ability to adapt to the client’s wishes and requirements.

In addition to the strong reputation he built around himself and his work, Anshelm became known for his unique ability to create a relationship between buildings and their surroundings. He always sought to integrate his structures with their environment and to achieve harmony. Klas Anshelm passed away in 1980, but his ideas and work continue to live on within Swedish architecture. His buildings still inspire and fascinate both architects and the public, and his perspective on the relationship between architecture, people, and place remains highly relevant today.

The exterior of Malmö Konsthall is characterized by its simple and clean design. Klas Anshelm’s original intention was for the art hall to harmonize with the City Theatre, now Malmö Opera, and a planned city hall with concrete details that was to be built adjacent to the art hall but never realized. Nevertheless, traces of Anshelm’s intended harmony with the site can still be seen in the choice of materials.

The building, constructed in concrete in a rectangular form, was often referred to by Anshelm himself as a “concrete box.” However, the straight lines of the façade are interrupted in places. On the façade facing Munkgatan, a V-shape was created, originally to make room for an elm tree that stood on the site before the building was constructed. The inclusion of nature in the architecture was no accident; Anshelm early on recognized the potential for the natural environment to harmonize with the building, a vision reflected in the texture of the concrete. The concrete was cast against wooden planks, resulting in a porous surface well suited for the climbing ivy planted on the façade.

The interior of Malmö Konsthall is designed to provide the best possible conditions both for the art on display and for the visitor’s experience. In many ways, the interior is an extension of the building’s minimalist and functional architecture. The central exhibition hall is a large, open “white box” with white walls and ceiling, creating a neutral setting that allows the art to take center stage. The flexible exhibition space makes it possible to adapt and transform the room for different types of installations and sculptural works.

With each exhibition, the impression of the interior changes. Walls are built and parts of the space are sectioned off, creating endless possibilities for spatial arrangements. When Malmö Konsthall opened in 1975, Klas Anshelm had designed modular walls that could be fixed to the floor and to the pipes running across the ceiling of the lower part of the exhibition hall. In recent years, similar movable walls have been constructed, allowing the space to be easily adapted and restored as needed.

Light plays a crucial role in the interior of the art hall. Thanks to the skylight construction in the ceiling, soft, natural light filters into the exhibition space. The quality of the light varies depending on the time of day and season, giving each exhibition and visit a unique atmosphere.

With its single-story layout, the art hall is designed with accessibility for all visitors in mind. The concept of “low thresholds,” often used to describe the institution’s approach, is also a reality in the physical space. The entrance airlock with two doors, which visitors pass through on their way into the main entrance, is an architectural device Anshelm frequently employed. The airlock has practical advantages – it prevents outside air from freely entering, helping to maintain the climate control within the exhibition space – but the low ceiling of the entrance also gives visitors a sense of greater openness when they step out into the exhibition hall.

The art hall’s floor is an architectural detail that has attracted particular attention from visitors over the years. As with several other material choices – concrete, glass, aluminum – the material is presented in its clear and unadorned form, creating a striking contrast with the white walls.

The floorboards are two-inch planed spruce from Småland, a choice the result of extensive discussions with suppliers from across Sweden. Anshelm intended the floor to be comfortable for visitors to walk on, while also being durable enough for the demands of exhibitions. It was designed so that nails, screws, or even walls and artworks could be attached without leaving significant marks. The floor is untreated; over the years it has been sanded a few times and regularly treated with soap between exhibitions. With its patina and history, the floor creates a lively and tactile impression—something Anshelm insisted on during the construction process, despite the art hall’s management preferring a painted wooden floor.

The risks associated with installing a floor of this type were addressed early in the construction process. To prevent the floorboards from expanding over time and potentially damaging the building’s structure, cuts were made parallel to the boards to accommodate any movement.

In several of Klas Anshelm’s earlier buildings, he employed a large roof lantern for natural light. This can be seen in Anshelm’s industrial buildings, such as Landsverk in Landskrona or Statens Maskinprovningar in Alnarp, as well as in Lunds Konsthall. Natural light is a consistent feature in Anshelm’s architecture. At Malmö Konsthall, a large roof lantern rises above the low, single-story building, with windows facing north. This design creates softer light, as direct sunlight never enters the space during the day. The similarity between his industrial buildings and the artist’s studio is evident; the indirect sunlight provides ideal conditions for the room. The robust columns supporting the window structure also create a sense of spaciousness, allowing for the presentation of larger installations.

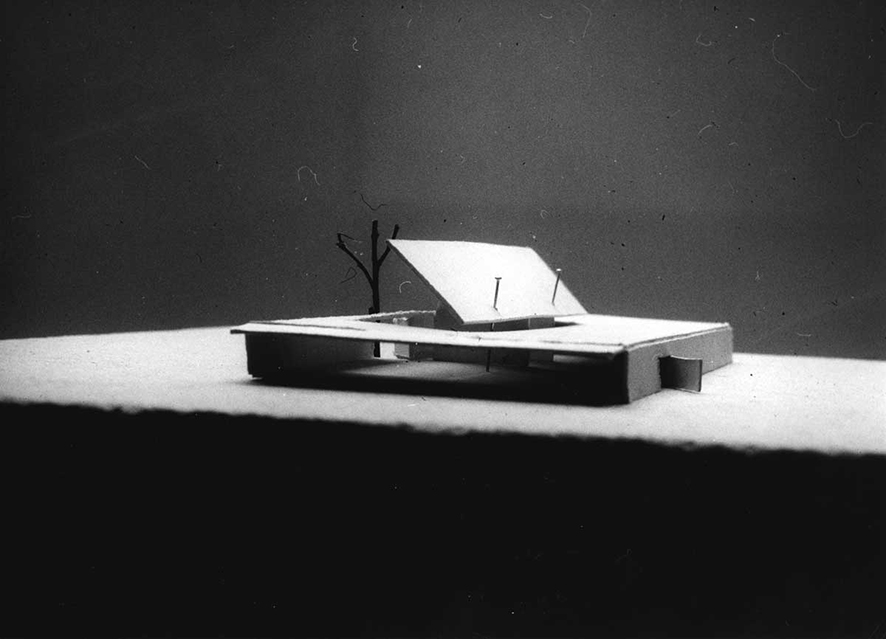

Ahead of the 1961 Venice Biennale, Anshelm was one of three architects invited to design the Nordic Pavilion. The other two were Sverre Fehn from Norway and Reima Pietilä from Finland. Anshelm received the commission request after having designed Lunds Konsthall a few years earlier. For the Scandinavian Pavilion, he proposed a special window construction intended to create unique lighting conditions. Angled glass panels were to be installed on the flat roof on the exterior, while each window on the interior would be fitted with a hood or kind of screen to diffuse and distribute the light down into the exhibition space.

Although he did not receive the commission, he carried the unique idea with him and later implemented it at Malmö Konsthall. The more than five hundred roof lanterns function like lampshades, distributing light down onto the floor. Each lantern can be darkened individually, allowing the lighting conditions to be fully adjusted to the needs of each exhibition.

Klas Anshelm aimed to create a large, durable space that could accommodate a wide range of activities. The art hall’s spacious and light-filled interiors provide room for artists to experiment with different materials, techniques, and forms of expression. As a studio, Malmö Konsthall functions as a place where artists can explore their ideas and work in an inspiring environment. The space offers resources and facilities to support the creative process, including tools, materials, and expertise. Artists from various disciplines and backgrounds have the opportunity to collaborate and exchange ideas, fostering a dynamic and stimulating working environment.

As an exhibition space, Malmö Konsthall is renowned for its groundbreaking and innovative contemporary art exhibitions. The hall presents works by internationally recognized artists as well as emerging talents across various art forms, including painting, sculpture, photography, video, and installation. Malmö Konsthall serves as a platform for showcasing artists’ visions and fostering a dialogue between artists and the public.

In 1994, the extension outside the original building designed by Klas Anshelm was inaugurated. Architect Jan Holmgren from White Arkitekter designed the addition, which connects the exhibition hall with the former Hantverkshuset from 1915. A new entrance into the art hall was also created through this extension. The architecture encloses two exterior wall structures and forms a new space, inspired by Anshelm’s choice of materials and his ideas about natural light and visibility through large window façades.

The renovation not only expanded the building but also refined the original exhibition space. The reception, café, and auditorium, which were previously located within the exhibition hall, were moved to what is now called “Mellanrummet” (The In-Between Space). Today, Malmö Konsthall’s bookshop is also located here, offering southern Sweden’s largest and most extensive selection of books on art. The In-Between Space, along with its auditorium (C-salen), now serves as a venue for lectures, presentations, and smaller exhibitions.

The interior of the In-Between Space was designed by furniture designer Åke Axelsson, whose work continues to define the character of the rooms today.

To the exhibition archive